Ultra-fast fashion charms young despite damaging environment

So-called "ultra-fast fashion" has won legions of young trend-setting fans who snap up relatively cheap clothes online amid surging inflation, but the booming genre masks darker environmental problems.

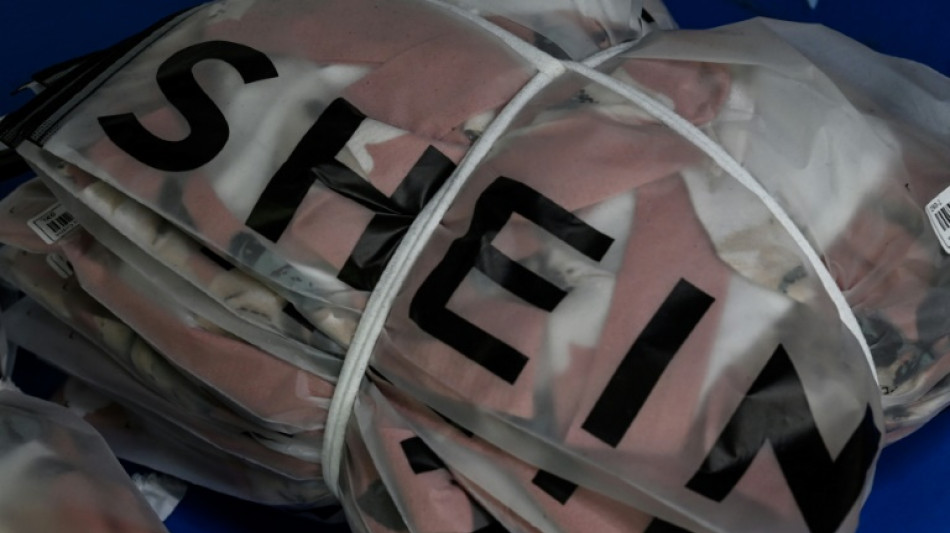

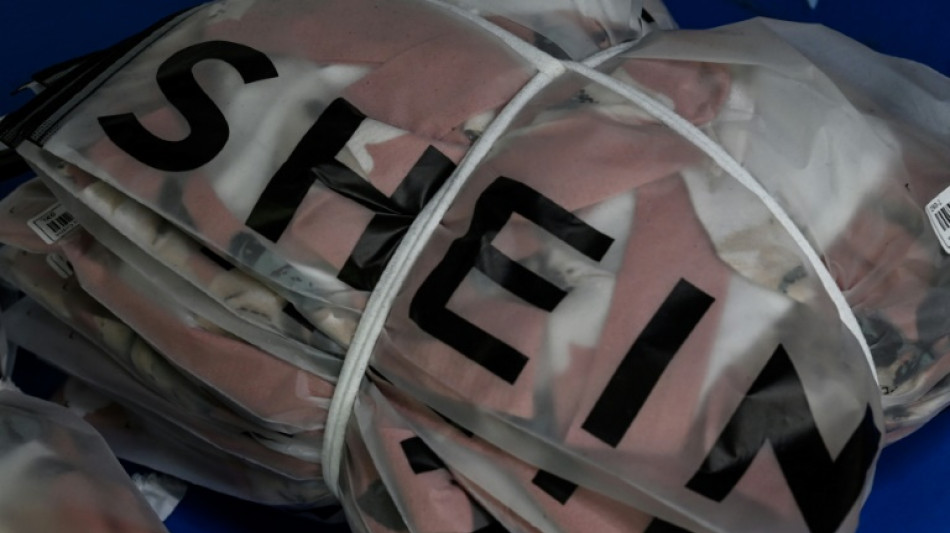

Britain's Boohoo, China's SHEIN and Hong Kong's Emmiol operate the same internet-based business model -- produce items and collections at breakneck speed and rock-bottom prices.

They are giving intense competition to more well-known "fast fashion" chains with physical stores, like Sweden's H&M and Spain's Zara.

Young people under the age of 25 -- widely known as Generation Z -- love placing multiple orders for ultra-fast fashion, which then arrive in the post.

- 'Consequences for planet' -

Greenpeace has, however, slammed the "throwaway clothing" phenomenon as grossly wasteful, arguing it takes 2,700 litres of water to make one T-shirt that is swiftly binned.

"Many of these cheap clothes end up... on huge dump sites, burnt on open fires, along riverbeds and washed out into the sea, with severe consequences for people and the planet," the green pressure group says.

Photographs of mountains of shoddy clothing, returned to the vendor or dumped soon after purchase, have gone viral, highlighting the vast amount of waste.

Demand for low-price garments has nevertheless soared due to decades-high inflation, while many Covid-hit high-street shops with big overhead costs struggle to compete.

And it is wildly popular: SHEIN generated $16 billion in global sales last year, Bloomberg says.

- Mirage of cheapness -

Customers purchase T-shirts for £4.0 ($4.80), while bikinis and dresses sell for as little as £8.0 apiece.

For French high-school student Lola, 18, who lives in the city of Nancy, SHEIN shopping has become a cheap hobby.

The brand simply allows her to follow the latest trends "without spending an astronomical amount", she told AFP, oblivious to the environmental cost.

Lola normally places two to three orders per month on SHEIN with an average combined value of 70 euros ($71) for about 10 items.

Ultra-fast fashion's young target demographic -- like Lola -- simply have less cash to spend.

Those consumers therefore "seek quantity rather than quality" of clothing, according to economics professor Valerie Guillard at Paris-Dauphine University.

SHEIN, which was founded in late 2008, now sells across the world helped by its massive presence on social media networks.

- 'Haul' videos -

Customers post so-called "haul" videos online -- where they unwrap SHEIN packages, try on clothes and review them.

That has boosted its popularity on TikTok, which is favoured by teenagers and young adults, while there are also such videos on Instagram and YouTube.

On TikTok alone, there are 34.4 billion mentions of the hashtag #SHEIN and six billion for #SHEINhaul.

Brands extends their reach via low-cost partnerships with a large number of people on social media, to build trust and increase sales.

Irish social-media influencer Marleen Gallagher, 45, who works with SHEIN and other firms, praised them for offering broader size ranges than regular stores.

"They are unrivalled when it come to choices for plus-size women," she told AFP.

- Climate emergency -

Yet the industry has a reputation for devouring valuable resources and damaging the environment.

Ultra-fast fashion companies have also been plagued by scandals over allegedly poor working conditions in their factories.

Swiss-based NGO Public Eye discovered in November 2022 that employees in some SHEIN factories worked up to 75 hours per week, in contravention of Chinese labour laws.

Britain's Boohoo also faced criticism following media reports that its suppliers were underpaying workers in Pakistan.

Added to the picture, the French Agency for Ecological Transition estimates that fast fashion accounts for a staggering two percent of global greenhouse emissions per year.

That is as much as air transport and maritime traffic combined.

The genre has meanwhile attracted the anger of climate campaigner Greta Thunberg.

"The fashion industry is a huge contributor to the climate and ecological emergency, not to mention its impact on the countless workers and communities who are being exploited around the world in order for some to enjoy fast fashion that many treat as disposables," Thunberg wrote last year, urging change.

P.Mueller--MP